The Do's

Be confident. You have the truth, which is not only a set of beliefs, but a Person who is pleased that you want to do the right thing, and will protect you.

Answer test questions as if you toed the party line on contraception, sterilization, and abortion. We can "prescribe" on paper.

Prepare an elevator speech so that whenever you must state your choices, you can do it smoothly and briefly.

(For residents) Tell your program director.

(For medical students) Do not tell any higher-ups unless you know they will be receptive. Tell clinic attendings at the beginning of any day (the evening before if possible) when there is an objectionable procedure scheduled; tell surgical attendings before the first sterilization you do with them.

Be an awesome person and a hard worker. We must "be perfect," to challenge those who think we're bizarre.

Find as much in common as possible. For instance, be loud proponents of "teens shouldn't get pregnant" and "STDs are terrible," and "no, condoms aren't enough!"

Counsel patients on family planning. To counsel is to present the dosing, routes, side effects, and mechanisms of action of available options. Counsel patients as frequently as possible, because only our counseling is truly presenting the whole truth about all three mechanisms of action (MOAs) of hormonal contraceptives (including thinning the endometrium which may lead to post-fertilization pregnancy loss, per the package inserts) and the existence and benefits of NFP or fertility awareness.

Happily volunteer to take out IUDs and nexplanons.

(For medical students and interns) You may observe one or two insertions of IUDs, nexplanons and Essure. Your participation is remote, it improves your counseling (i.e. you won't remember to mention ibuprofen premedication before IUD insertion if you don't realize quite how much cramping can occur), and you can pray for the patient and physician more vehemently. Students, it's best to speak with your preceptor beforehand, as soon as you see an IUD/nexplanon/Essure insertion on the schedule. If somehow that doesn't happen and you're offered the chance to do the procedure, just say, "I'm not comfortable." (Residents, your PD should already know.) But (students) if they press you (and residents, if this attending didn't get the memo), say confidently: "Thanks for the chance! But I'm choosing not to prescribe contraceptives."

You can participate in endometrial ablations. These are usually done for gynecological pathology (e.g. excessive menstruation) and are not a form of sterilization; however, they do have a sterilizing effect. If everyone's intentions are correct, the principle of double effect at work. Because we cannot see into other souls, we can pray for the best and operate as if the principle applies. (If the patient makes it clear that she wants the sterilizing effect, it's your duty to tell her that this procedure does not sterilize and you cannot guarantee that.)

You can participate in hysterectomies. Everything that applies to ablations applies also to it. Our bodily integrity is important, but this procedure is sometimes necessary for patients who fail conservative management (i.e. ibuprofen, lysteda, napro).

.jpg/1024px-CPMC_Surgery_(412142792).jpg) You can scrub into C-sections during which they plan to do a tubal ligation (BTL). You can assist with the section, but do not do anything during the BTL. To protect yourself from acting during the BTL, speak with your attending or chief resident (whoever the highest person in the room will be) beforehand.

You can scrub into C-sections during which they plan to do a tubal ligation (BTL). You can assist with the section, but do not do anything during the BTL. To protect yourself from acting during the BTL, speak with your attending or chief resident (whoever the highest person in the room will be) beforehand.(For medical students) Some attendings will not let you scrub because you're refusing to participate in the BTL. This is unjust, but take it gracefully and ask if you can observe. If they say no, go peacefully back to the floor or L&D.

(For residents and sub-interns) You can scrub into a BTL to practice laparoscopic access techniques. Make it clear to your attending that you will not be participating in the ligation, but are grateful for the opportunity to learn from their experience in entering and closing the abdomen safely.

You can participate in dilation and curretage (D&C) when done for missed abortion (miscarriage). There is no moral quandary here, if fetal death has been verified by lost heart tones, absent cardiac motion, negative hCG, obvious ultrasound findings (e.g. separation suggesting the decay of remains), or obvious history (e.g. three days of heavy bleeding with fetal parts). Always say to the mother and father of the child, "I'm sorry for your loss." Not only is this what they feel, but it builds up the identity of the unborn child as a person.

Obviously, you can participate in D&C for non-obstetric indications or retained placenta.

(Not usually for students) You can induce labor for missed abortion. If the loss is verified as above, console the patient and father and help with cervical ripening and augmentation.

Counsel on elective abortion (EAB). You must know at what gestational age different procedures (RU486 (mifepristone), D&C, and dilation and extraction (D&E)) can be done. You must be able to describe these techniques to women gently but without euphemism. You must also know the rates of post-traumatic stress symptoms and PTSD among abortion victims, the rates of live birth following abortions, and (if you're a gunner) laws in your state about waiting period, parental notification/consent, ultrasound, and upper gestational age limit.

Care for EAB patients before and after their abortions. This includes preop and postop care in the hospital, and follow-up visits in clinic. Ask about how the patient is handling the loss. Be ready to offer local post-abortive healing information (i.e. carry the cards with you in your pocket), but don't push it.

You can participate in training activities for D&C and LARC/Essure insertions. A D&C is a legitimate operation for indications like excessive bleeding and missed abortion, and scooping out a papaya to learn how to do it is not a big deal. Mirena can help nonsexually active patients who fail other pharmacological therapies. Pick your battles and don't fuss about this. Use it as a chance to observe to your peers sitting next to you about how weird it is that you'd do a D&C when there's still a heartbeat, or how there's gotta be some way to plan pregnancy without sticking a 16 gauge needle in someone's arm (nexplanon).

Counsel on perinatal hospice. Perinatal hospice should be offered to any patient with a fetal anomaly that is "incompatible with life." This is a period of parenting the unborn child and mourning the loss of the baby the parents hoped for. It also involves services like Now I Lay me Down to Sleep (a no-charge project). Students and residents have a particular power in suggesting perinatal hospice (which is uncommon at most centers that offer termination for lethal anomalies) because we go in before the attending and can make suggestions that the attending would not.

(For residents) You can consent patients for BTLs and IUD/nexplanon insertions. To consent (like to counsel) is to offer a full picture of risks, benefits, and alternatives. We are the ideal people to consent for BTLs, nexplanon insertions, and IUD insertions, because we can stress that these things affect something valuable (fertility and integrity of lovemaking), and we can emphasize the permanence of sterilizations, and the fact that many regret their procedures. If you help a patient opt into a less permanent form of birth control, you've helped! It's painful to consent and counsel when people make the wrong decision. But we can only offer the truth (the whole truth), and allow our patients and our superiors to make their own decisions.

|

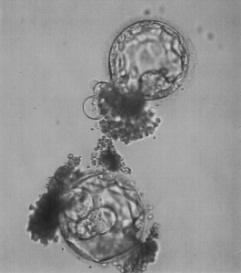

| Wikimedia. The contributor writes: "This is an image of my child, he died and this is how I remember him." |

Pray every day. 30 minutes of mental prayer keeps you moving towards sanctity. (St. Theresa said that if we meditate, we will either become saints or stop meditating.) If I'm an OB intern and I can do it, so can you.

Talk it out with a friend. If the attendings are making you feel unwelcome, if you're stressed, if the culture is asphyxiating...get it off your chest! Get coffee with a friend and vent! If you don't have anyone sympathetic, email me. (That address is permanent, so even if you're reading this ten years after I wrote the post, I'll get it.)

Contact Alliance Defending Freedom if you're truly discriminated against.

Be patient with yourself. You can't solve all the patients' problems or correct all your own inabilities all at once! Christ has the power to make up for your defects. Ask Him to do so, go to confession, and move forward in peace.

The Don'ts

Don't make assumptions about sinners' intentions. (This includes patients, peers, and attendings.)

Don't proselytize. Be attractive as a good student/resident, then be unafraid when people ask about NFP or the Catholic Church's ideas on contraception.

Do not advise the use of any hormonal contraceptive (e.g. mirena) in sexually active patients. Period. This is because of their post-fertilization effects.

Do not promote barrier contraceptive use as a good in itself. As Pope Emeritus Benedict wrote, condom use can be a step towards chastity, but always hold up abstinence as an ideal for the unmarried and NFP as an ideal for the married.

(For medical students) Try not attend more than two IUD insertions, more than two nexplanon insertions, and more than two essure insertions. Frame it as sharing with the other med students, or go find something helpful to do on the floor. Make something up if you can't find anything legitimate to do ("I have to go bring this down to the radiology library," "I have to fax this paperwork"), because it's important to not overexpose yourself. You don't want to dispose yourself to think these things are okay.

Do not participate in egg harvests, male masturbation, intrauterine inseminations (IUIs) and other gamete transfers, or in-vitro fertilization. Medical students should not put themselves in this situation: do not do an REI rotation at a facility that does IVF. Residents: if you must observe, make it clear to the attending that you cannot participate, even by holding the transducer.

(For residents) Do not induce labor for inevitable abortion, i.e. when fetal death has not occurred (e.g. when there are still heart tones).

|

| This is a miscarried baby, not an EAB victim. |

(Mostly for medical students) Don't disrupt a patient-doctor relationship. This means that if your attending prescribes contraceptives to a long-time private patient, don't go into the room and talk about the carcinogenicity of hormones and the irresponsibility of using them. This will scare or frustrate the patient, make your attending unhappy with you, and cast a shadow on the truth about fertility awareness. This item not is on the list is because we want to be happy and comfortable. It's because a trainee has limited abilities to help people make good family planning choices; trying to break out of those limits will likely not help you become a physician, or a saint.

Don't dump any other task on others.

Don't be frustrated when people assume you're making these choices for stupid reasons. Most will assume you're choosing unfounded cultural/personal opinions over science. Take it gracefully, and remember that when you suffer it is because Christ is bringing you close to Him in His Passion.

I hope this post is helpful. I will edit it periodically to reflect new devices and laws as the need arises. I want to fill in some of the numbers and am working on finding the literature behind them so that I don't put unfounded figures in your mouth. Please leave a comment below if you've run into a situation I haven't covered.

.jpg/800px-Medical_students_learning_about_stitches_(2760577402).jpg)

.png)