The Hiding Place is the story of a Catholic watch maker who sheltered Jews during the Holocaust. She was taken to a concentration camp, where she was put to work on an assembly line. As a watch-maker, she took easily to the assembly of relay switches. Too easily. She recounts how her foreman, a fellow prisoner, reacted:

The Hiding Place is the story of a Catholic watch maker who sheltered Jews during the Holocaust. She was taken to a concentration camp, where she was put to work on an assembly line. As a watch-maker, she took easily to the assembly of relay switches. Too easily. She recounts how her foreman, a fellow prisoner, reacted:"Dear watch-lady! Can you not remember for whom you are working? These radios are for their fighter planes!" And reaching across me he would yank a wire from its housing or twist a tiny tube from an assembly. "Now solder them back wrong. And not so fast! You're over the day's quota already and it's not yet noon."I am a pretty good intern. I can see seven postpartum patients in an hour and a half, consent half of them for circumcision, counsel half of them on family planning options, discharge half of them, write their orders, finish and route their notes appropriately, and present them coherently at morning rounds. I still miss a detail here and there. But overall, I'm pretty good at what I do.

I can even consent for tubal ligation and arrange the paperwork for the two different states in our catchment area. (I have previously opined that it is not morally wrong to consent patients for BTLs.) But should I be this awesome at hooking people up with sterilizations? Should I be making it harder for people to get BTLs and, for that matter, contraceptives?

"Dear intern!" I hear in my head, "Can you not remember for whom those sterilization papers/OCPs/LARCs work? Those break down marriage and the family!" Many thoughts have flown in the past few weeks about whether I should yank some wires. (Note that I am not comparing my attendings and fellow residents to Nazis. I am only opposed to sterilization, not the people who do it.)

|

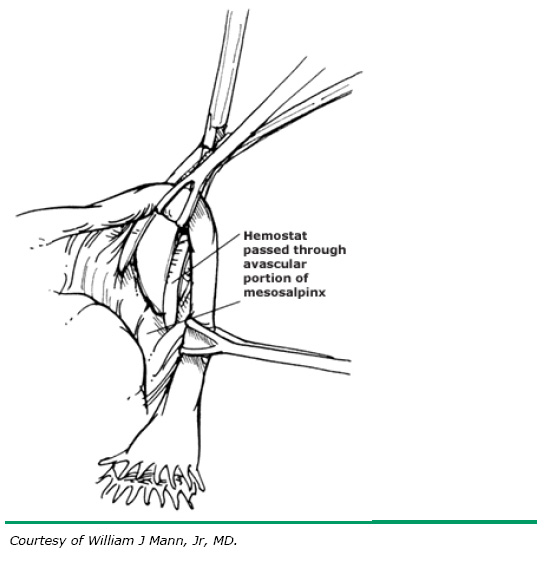

| Thanks to: ama.uk.com and uptodate |

On the other hand, a little slip in the paperwork and someone could be delayed in receiving a BTL just long enough to have a different thought about it. One in five women who choose BTL within a year of their delivery regret it. And permanent primary sterilization is a grave evil even if someone doesn't rethink it. Did Corrie ten Boom care whether she'd be punished for soldering the wires wrong?

In the end, I decided to apply the principles I apply to any other consent: I counsel completely and accurately, I give the patient time (e.g. I tell them to think about it and talk with at least one other family member on postpartum day 1 and/or 2) and I fill out the paperwork if the patient chooses on the last day I see her. I have had patients who say (after I talk with them), "I decided not to, I'll just go with the [other method, usually a LARC]." I'm not happy about the LARC, but I am full of joy that I can throw away their BTL consent and hope that they learn to appreciate their fertility in the time they've afforded themselves.

Some disagree with me about whether BTLs are good for women, and others disagree with any involvement in the process. But I doubt that many would disagree with my approach to postpartum tubal consents: I counsel completely, give the patient time to make their own, informed decision (and speak with the attending after I see them, who usually offers a different opinion). I then witness when they make this decision on a form for the state.