Some don't know that section 15 of Humana Vitae reads:

On the other hand, the Church does not consider at all illicit the use of those therapeutic means necessary to cure bodily diseases, even if a foreseeable impediment to procreation should result there from—provided such impediment is not directly intended for any motive whatsoever.And some don't realize that this doesn't answer the question.

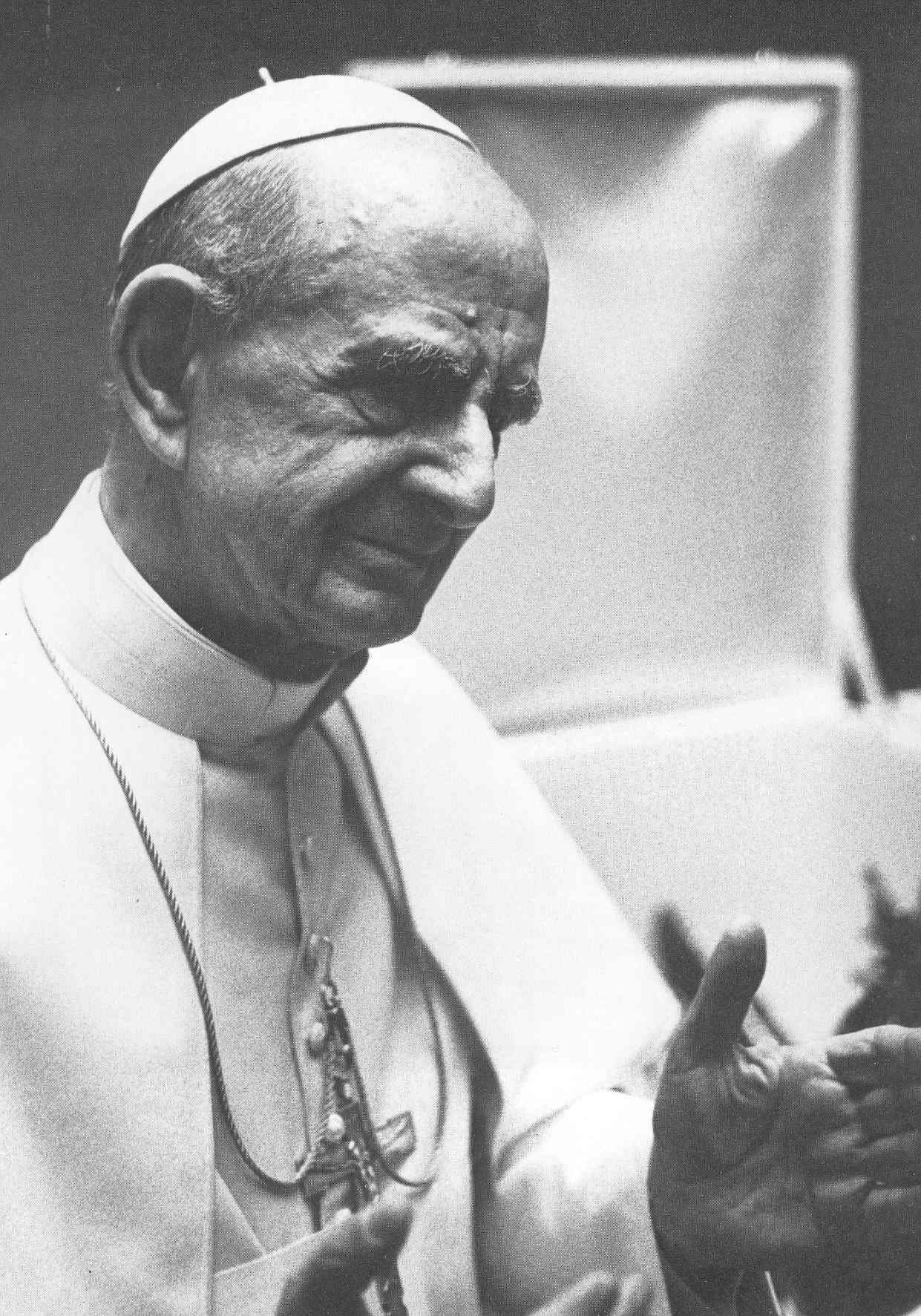

Pope Paul VI wrote HV before the post-fertilization effects of the pill were well known, before the controversy over its side-effects, before four decades of gynecological advancement, and before lower-dose pills (in early trials, pills contained the estrogen of three high-dose pills on todays market, and the progestin of ten Plan B One-steps). We can still apply his intention, but we need to ask the question again: should we use the pills currently available as we currently do?

First of all, let's cover some basics.

- What is a "medical purpose?"

- What is "treatment?" What is "cure?"

- What medical purposes are usually included in this discussion?

"Medical purpose" is a vague phrase. Merriam-Webster defines medical as "relating to the treatment of diseases and injuries," and purpose as the intention (the reason and hoped-for end point) of an action. Taking an action for a "medical purpose" must have treatment of disease as its intention.

What is treatment? In an editorial of precisely that title, a pediatrician named John Knowles wrote the American Academy of Pediatrics, just around the time that Pope Paul VI was writing HV. The piece is pithy and relevant:

To "cure" is a relatively familiar concept, thanks to lots of oncology marketing. It means "to make someone healthy again."

Hormonal contraceptives are often regarded as treatment (or "standard of care") for gynecological problems like fibroids (235 million women worldwide), abnormal uterine bleeding (53 per 1000 women in the U.S.), dysmenorrhea (25% of women), polycystic ovarian syndrome (116 million women worldwide), and endometriosis (6-50% of women, depending on the population). (Not ovarian cancer.) Many Catholic ethicists and activists will repeat that hormonal contraceptives remove the symptoms of these disorders without changing the underlying cause. This is mostly true.

The gynecological disorders just mentioned are problematic because of cyclic hormones--her own hormonal factories are over- or under-firing, to her body's detriment. Hormonal contraceptives supply an artificial set of hormones, suppressing the patient's hormones and stopping the cyclic problem. (This is an over-simplified explanation for the multi-system, multifactorial PCOS, but is a decent explanation of the others.) This means hormonal contraceptives do address the cause of the disease: they silence the woman's production of hormones. But they don't cure: they don't repair the woman's organs so that she can cycle naturally and healthily on her own. The goal for women on hormonal contraceptives is either indefinite prescriptions, or to stop at some point (usually when fertility is desired) and hope for resolution of symptoms.

Hormonal contraceptives are also prescribed while women are taking teratogenic medications prescribed for other conditions (e.g. methotrexate for lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or cancer; accutane for acne). Here, they do not treat the medical condition, but are used to prevent conception while the woman is taking something that would lead to birth defects or spontaneous abortion. (The irony of using something with post-fertilization effects to prevent spontaneous abortion should be obvious.)

Now let's answer the questions.

What is treatment? In an editorial of precisely that title, a pediatrician named John Knowles wrote the American Academy of Pediatrics, just around the time that Pope Paul VI was writing HV. The piece is pithy and relevant:

[A]n increasing number of physicians are equating good treatment practices solely with specific drug therapy. This is recognizable most often in the use of the word treatment as synonymous with antibiotic. "No, I'm not 'treating' him" too often means "No, I'm not giving him any antibiotic." ...[The] personal bias of the physician [impacts] his philosophy and policies in respect to the treatment of his patients [but] let us not confuse the patient or ourselves by equation of a specific modality of therapy in which we happen to have transient faith with the total treatment rendered by careful analysis and responsible advice. [Physicians] have both a privileged advantage and a responsibility in developing a realistic appreciation of "what medical care is" in their patients....Treatment, says Dr. Knowles, begins with our first contact of the patient, continues in our listening, exam, workup, and dialogue, and culminates in executing a plan for the patient's care. Knowles tells the story of a resident who develops a detailed plan for a young patient with a viral infection, and confesses at the end of the conversation to the patient's mother that "I don't think I will treat her at this time," meaning that he would not give an antibiotic. Knowles condemns this attitude, stating that the resident had treated the patient completely, and describing use of antibiotics as "treatment" was a mistake.

To "cure" is a relatively familiar concept, thanks to lots of oncology marketing. It means "to make someone healthy again."

Hormonal contraceptives are often regarded as treatment (or "standard of care") for gynecological problems like fibroids (235 million women worldwide), abnormal uterine bleeding (53 per 1000 women in the U.S.), dysmenorrhea (25% of women), polycystic ovarian syndrome (116 million women worldwide), and endometriosis (6-50% of women, depending on the population). (Not ovarian cancer.) Many Catholic ethicists and activists will repeat that hormonal contraceptives remove the symptoms of these disorders without changing the underlying cause. This is mostly true.

The gynecological disorders just mentioned are problematic because of cyclic hormones--her own hormonal factories are over- or under-firing, to her body's detriment. Hormonal contraceptives supply an artificial set of hormones, suppressing the patient's hormones and stopping the cyclic problem. (This is an over-simplified explanation for the multi-system, multifactorial PCOS, but is a decent explanation of the others.) This means hormonal contraceptives do address the cause of the disease: they silence the woman's production of hormones. But they don't cure: they don't repair the woman's organs so that she can cycle naturally and healthily on her own. The goal for women on hormonal contraceptives is either indefinite prescriptions, or to stop at some point (usually when fertility is desired) and hope for resolution of symptoms.

Hormonal contraceptives are also prescribed while women are taking teratogenic medications prescribed for other conditions (e.g. methotrexate for lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or cancer; accutane for acne). Here, they do not treat the medical condition, but are used to prevent conception while the woman is taking something that would lead to birth defects or spontaneous abortion. (The irony of using something with post-fertilization effects to prevent spontaneous abortion should be obvious.)

Now let's answer the questions.

- Are contraceptives the only option for gynecological abnormalities?

- What about contraceptives for medically-indicated teratogens?

We're not in 1968 any more, and there's something better than hormonal contraceptives. As a reminder, hormonal contraceptives replace a woman's own cycle with pregnant-like levels of modified steroid hormones. In doing so (even for good purposes!) they adversely affect fertility and can lead to early pregnancy loss.

But that's not the only option. Gynecologists who want to can target specific times in a woman's cycle, if she's aware of the signs and symptoms of her own fertility. With those times identified, the physician can identify (by blood test) hormonal deficiencies, then supplement (by oral, vaginal, or intramuscular injection) individual cycles on time. Because this approach respects the timing of the woman's cycle, it does not affect her fertility. (In fact, especially in the case of PCOS, it may give it back.) The goal for women who are treated like this is slow weaning off of hormonal support, so that they can cycle normally on their own.

What about women taking contraceptives because they are also taking a medication that can cause severe birth defects? Women who need isotretinoin for disfiguring acne (which pulls some out of depression and bad social situations) or who need methotrexate for disabling autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus are often told they must be on two forms of birth control. 300,000 women used isotretinoin in 2000, almost all of whom were of reproductive age (more recent data are not available). I couldn't find good statistics on methotrexate use, but I hazard a guess that approximately 2 million women of reproductive age used it last year for cancer and autoimmune conditions.

Accutane leads to a syndrome of malformations of the face, heart, and nervous system; methotrexate, to one of craniofacial and extremity malformations (both are also abortifacient, causing miscarriages). In cases of pregnancy during either therapy, physicians are taught to offer elective abortion (termination) to their patients.

This standard of care is noticeably contradictory in its approach to the value of an embryo. Embryos are valuable and do not deserve to be exposed to harmful chemicals, so do not become pregnant. Embryos are not valuable, so use a contraceptive which can cause their early demise. Embryos are valuable, so March of Dimes is indignant that miscarriages occur with accutane. Embryos are not valuable, so abortion is an option.

That can of worms discussion is beyond the scope of this post; it's enough to say that fertility awareness based methods of avoiding pregnancy are 93-99.5% effective when used correctly, and don't carry all the ethical baggage of hormonal contraceptives. Not only that, but they offer hope of cure, without replacing a woman's own cycle, without post-fertilization effects, and (for the Catholics) without separating spousal love and fertility.

So the answer? I can't be sure; if naprotechnology was the standard of care, maybe zero.