The OB/GYN who I mentioned typed up some advice for all of us at the Vita Institute. Being pro-life, he said, has to do with treating all people like the Lord Jesus. It is really not separate from being a Christian. To lower teen pregnancy rates and improve the culture around us, we must dutifully answer Christ's call in all circumstances and with all people.

Email me for a copy of the document he wrote summarizing his comments.

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Friday, August 26, 2011

Med Student Life and Premed Questions, pt 2

Third and fourth year. Today I shadowed a third-year as she rotated her fourth week in pediatrics. I followed her in an outpatient setting. She had a good deal of independence. (She plotted growth/height milestones, decided which shots the child should have, saw the patient, took a history, did a physical exam, counseled parents, and then presented to the doctor. The doctor then checked her work and repeated an abbreviated version of this to make sure everything was covered satisfactorily.)

She told me that she spends about half her time in the hospital (inpatient) and half in the clinic (outpatient). She is on call two weekday evenings (5:00pm to 11:00pm) and one weekend (8:00am to 11:00pm); during this time, she has to be within 20 minutes of the hospital and have her cell phone with her (they can now use phones instead of pagers). On the weekend call day, she visits each hospitalized patient (a.k.a. she "rounds" on them or she "does rounds") and assesses their progress. The doctor checks her notes and she goes home (just a few hours in the hospital). Overall, her assessment of peds was "pretty gentle."

She impressed me. She wasn't as smooth as the physician but she knew all kinds of questions I wouldn't have thought to ask, she could listen to heart sounds in the right places, and present like a pro. "This is a six-year-old male who came in with a firm, non-erythematous swelling of the third digit of the right hand, retaining full range of motion...possible bone fracture, rule out...." At the same time, I knew that she was not too different from me. She was a little nervous, she reviewed her books between presentations, and she half-bluffed some of those heart sounds (I'm not completely blind...). I have a lot of hard work to do, but I think I can become like her eventually. (By the way, I didn't know there were books like hers, books not on science but just about clinical pediatrics or obstetrics or whatever. How nice! That means I don't have to store it all in my brain. Just most of it....)

Ask third- and fourth-years what their rotations are like: what is a typical day? are you in the hospital or the clinic more? are you independent? how much? do you like that? are you on call? what nights/days/weekends are you on call? do you rotate alone or with a group? how many students per faculty member on these rotations? do you enjoy their time or feel pressured? why did you choose to do rotations in the order you did? did you get your first choice of rotation orders? do you know what specialty they want to enter?

She told me that she spends about half her time in the hospital (inpatient) and half in the clinic (outpatient). She is on call two weekday evenings (5:00pm to 11:00pm) and one weekend (8:00am to 11:00pm); during this time, she has to be within 20 minutes of the hospital and have her cell phone with her (they can now use phones instead of pagers). On the weekend call day, she visits each hospitalized patient (a.k.a. she "rounds" on them or she "does rounds") and assesses their progress. The doctor checks her notes and she goes home (just a few hours in the hospital). Overall, her assessment of peds was "pretty gentle."

She impressed me. She wasn't as smooth as the physician but she knew all kinds of questions I wouldn't have thought to ask, she could listen to heart sounds in the right places, and present like a pro. "This is a six-year-old male who came in with a firm, non-erythematous swelling of the third digit of the right hand, retaining full range of motion...possible bone fracture, rule out...." At the same time, I knew that she was not too different from me. She was a little nervous, she reviewed her books between presentations, and she half-bluffed some of those heart sounds (I'm not completely blind...). I have a lot of hard work to do, but I think I can become like her eventually. (By the way, I didn't know there were books like hers, books not on science but just about clinical pediatrics or obstetrics or whatever. How nice! That means I don't have to store it all in my brain. Just most of it....)

Ask third- and fourth-years what their rotations are like: what is a typical day? are you in the hospital or the clinic more? are you independent? how much? do you like that? are you on call? what nights/days/weekends are you on call? do you rotate alone or with a group? how many students per faculty member on these rotations? do you enjoy their time or feel pressured? why did you choose to do rotations in the order you did? did you get your first choice of rotation orders? do you know what specialty they want to enter?

Med Student Life and Premed Questions, pt 1

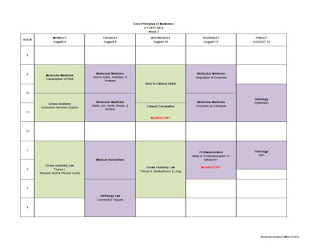

First and second year. One of the things I really wanted to know as a premed was what med students' schedules look like. I have attached my schedule for this week and next week as pictures. We have a block curriculum and have tests every two or three weeks. Click to enlarge.

Premeds: ask the first- and second-years (not the people who present the curriculum) what the curriculum is like: how often do you have tests? do you learn by system, by region, by clinical presentation...? when do you get clinical skills? do you have problem-based learning or clinical correlations? are you required to shadow or volunteer? when do you see standardized patients or use the simulation center? are the students competitive?

Premeds: ask the first- and second-years (not the people who present the curriculum) what the curriculum is like: how often do you have tests? do you learn by system, by region, by clinical presentation...? when do you get clinical skills? do you have problem-based learning or clinical correlations? are you required to shadow or volunteer? when do you see standardized patients or use the simulation center? are the students competitive?

Stats on the first test

Little objective to go with my subjective. Maybe this will make people more nervous...hmm....

There are two portions to our exam: a 100-question written (multiple choice) test and an 80-question practical (powerpoint slides and fill-in-the-blanks). The class average for our written was a 77; for our practical, 73. Our overall average block grade (grade for the course) is 80, but this will move down as the 10% that the quizzes contribute becomes less relatively important.

There are two portions to our exam: a 100-question written (multiple choice) test and an 80-question practical (powerpoint slides and fill-in-the-blanks). The class average for our written was a 77; for our practical, 73. Our overall average block grade (grade for the course) is 80, but this will move down as the 10% that the quizzes contribute becomes less relatively important.

Thoughts on the first test

Our first test was August 19 (a week ago today). Outwardly, I sometimes became pretty nervous: during a private review my tank (my lab group assigned to a cadaver) had with one of the anatomy professors (the most respected one), I thought I was going to fail. He quizzed us mercilessly: some questions I couldn't answer, others I was too squeaky and scared to answer, and still others made me worried I hadn't studied any of the right stuff to the necessary depth.

He asked some verbal questions, but would also just hand one of us a pin and say "find the [insert structure here on the cadaver in front of us]." He asked me to find the left recurrent laryngeal nerve. I looked in the right spot, and everything seemed so shredded and uniform--I pinned my best guess and straightened up. He gave a cool and casual look at my attempt, then met my eyes with a look that drilled fear into my soul. "Wrong," he said simply. I felt like jelly. I bent over the pin again and (motivated by sheer terror) found the nerve the second time--thank goodness.

I tried to put my fear behind me. But it seems like everyone thought this test was impossible. The M2's said things like, “don't worry, the first test--everybody messes up. It gets better.” “Don't cry.” "There's a learning curve.” “You just have to figure out how to study.” “The last in the class is still called ‘doctor.’” I thought I must be doing something wrong, since I felt pretty normal about what I'd learned. I would get to the test and the questions would be impossible, involving tricks and slips that I could only dream of.

Remember Freud's parapraxes? I did nothing else in the week leading up to the test.

He asked some verbal questions, but would also just hand one of us a pin and say "find the [insert structure here on the cadaver in front of us]." He asked me to find the left recurrent laryngeal nerve. I looked in the right spot, and everything seemed so shredded and uniform--I pinned my best guess and straightened up. He gave a cool and casual look at my attempt, then met my eyes with a look that drilled fear into my soul. "Wrong," he said simply. I felt like jelly. I bent over the pin again and (motivated by sheer terror) found the nerve the second time--thank goodness.

I tried to put my fear behind me. But it seems like everyone thought this test was impossible. The M2's said things like, “don't worry, the first test--everybody messes up. It gets better.” “Don't cry.” "There's a learning curve.” “You just have to figure out how to study.” “The last in the class is still called ‘doctor.’” I thought I must be doing something wrong, since I felt pretty normal about what I'd learned. I would get to the test and the questions would be impossible, involving tricks and slips that I could only dream of.

Remember Freud's parapraxes? I did nothing else in the week leading up to the test.

- T-7: lost my ID to the anatomy building (bad news for a room that's governed by state law as to who can go in; luckily a lady found it and I got it back the following monday)

- T-2: hit a car in one campus parking lot

- T-1: set fire to my toaster oven. Fire. I'd never been in a fire before. The apartment was full of smoke, everything (including me) smelled like smoke, the oven (never mind the breakfast) was blackened....

- T-1: hit another car in the other campus parking lot

- The day before our grades were scheduled to come out: locked my keys in my car, called a locksmith at 10:00pm.

Bottom line

(future medical students, especially TACers):

DO NOT BE NERVOUS.

St. Pio says it like this: “Worry is useless.” And read Matthew 6:25-34! Do your best: truly make an effort, and this will be good.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

OB/GYN interest group!

There's an OB/GYN club, yay! They have a cool mentorship program and they do workshops and talks and stuff, so I'm super excited.

Also, I ran for M1 representative, and won! Wow...now I have to work!

Also, I ran for M1 representative, and won! Wow...now I have to work!

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Healthcare system lecture....bleargh...

Today we had a lecture by the immediate past president of the AMA. Very interesting. Very scary.

Much of his lecture was focused on the history of nationalized healthcare and healthcare as a right. He went through the AMA principles of medical ethics. I remember discussing these at TAC--they were the first substrate of the TAC Medical Society's discussion series. We contrasted them to the Hippocratic Oath. Contrasted them. To my mind, they do subtle harm to the duties of a physician. (That is probably another post.)

Much of his lecture was based on audience-response technology (instant voting through our laptops/phones). I think most of his questions were frustratingly vague and slanted. Here are the most interesting of them, along with the class' responses (n~200 first-year medical students).

Much of his lecture was focused on the history of nationalized healthcare and healthcare as a right. He went through the AMA principles of medical ethics. I remember discussing these at TAC--they were the first substrate of the TAC Medical Society's discussion series. We contrasted them to the Hippocratic Oath. Contrasted them. To my mind, they do subtle harm to the duties of a physician. (That is probably another post.)

Much of his lecture was based on audience-response technology (instant voting through our laptops/phones). I think most of his questions were frustratingly vague and slanted. Here are the most interesting of them, along with the class' responses (n~200 first-year medical students).

- Is healthcare a right or a privilege?

67% voted "right"

33% voted "privilege"

- What is the most important unalienable right of an individual?

54% voted "life"

30% voted "liberty"

15% voted "pursuit of happiness"

- Would you order a medically unnecessary test to pay the bills?

4% voted "yes"

96% voted "no"

- Does AMA Principle III obligate every physician to be involved in the American political system?

47% voted "yes"

53% voted "no"

- A patient presents with an emergency condition and needs medical care that is against the personal beliefs of the physician and there is not time ot find another physicain. Should the physician provide the medically necessary care?

86% voted "yes"

14% voted "no"

- Equitable care eliminates disparity. A major driver of disparity is lack of health insurance. Thus, all Americans must have health insurance to eliminate health disparities.

52% voted "yes"

27% voted "no"

Sunday, August 21, 2011

At Knock: Our Lady of Silence - Vultus Christi

I enjoyed this article about Our Lady of Knock. One doesn't hear much about this apparition, but this message (holy silence gazing on God) is sorely needed for salvation. Mary teaches us this in the Gospels, and in this apparition she shows us again.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

No nature

We had a lecture today on the genetics and ethics of mental illness. Mostly it was about informed consent, eugenics, and genomic medicine. But I was disturbed by two things in the philosophy of medicine assumed.

There is a relativistic view of health and illness in medicine. It seems especially difficult to avoid in psychiatry. In this view, "health" and "disease" are on a sort of spectrum, and people are somewhere on the spectrum. On this spectrum, it's somewhat arbitrary what is "healthy" and what is not. The border between loose connective tissue and dense irregular connective tissue in the dermis is somewhat arbitrary--it's more like a gradient, but the professor always draws a line across the picture somewhere. Similarly, the clinician or laboratory or government agency decides what "healthy" is, and what "diseased" is.

It's very easy to think this, because our imaginations lend a lot of credence to it. But it's not true. Health and sickness are like virtue and vice or water and oil: immiscible. A healthy person is like a glass of water; a sick person is like a cup of oil. Granted, there are lots of kinds of oil, and some are less viscous than others and resemble water much more. (The analogy limps because a sick person can become healthy and vis a versa; last time I checked the literature, a cup of water cannot become a cup of oil.)

Another problem was the blatant assumption that disease is largely determined by culture. The lecturer quoted the subtraction of homosexuality from the DSM as an example. (In 1973, demonstrations and protests pressured the American Psychiatric Association to review the literature and vote on the diagnosis.) This is indeed an example of a culture determining what is called a disease. It is not an example of a culture determining what is a disease.

What is and is not a disease is not determined by any person or any culture. It is determined by the nature of man (the internal principle of motion). For instance: a mechanic determines whether or not a car is broken based on the car's intended function. He does not consult the cultural norms for what is accepted; he does not vote with his fellow mechanics about it. Similarly, physicians ought not to consult the cultural norms when they identify disease states, nor ought they to vote among themselves. The should consult man's nature and determine whether a state is compatible with man's natural (intended) function.

(As an aside: homosexuality doesn't take much thought if considered this way. Man is male and female by nature, and designed for heterosexual union.)

What was the APA considering in 1973? Previous to this lecture, I did not know. Now, I do: the qualification for mental disease is inability to function in life. (The lecturer cited an example to drive this point home: if a person presents with classical schizoprenia--hallucinations, delusions, genetic predispositions, the works--but can function normally, they don't have it. According to this speaker, most of the DSM entries are now modified with this criterion: the patient must be dysfunctional according to generally accepted norms.) Gays, the APA said in '73, were able to function and felt quite accepted and normal. Therefore, they were not mentally diseased.

There is no nature in psychiatry, and I fear there is little more in medicine.

There is a relativistic view of health and illness in medicine. It seems especially difficult to avoid in psychiatry. In this view, "health" and "disease" are on a sort of spectrum, and people are somewhere on the spectrum. On this spectrum, it's somewhat arbitrary what is "healthy" and what is not. The border between loose connective tissue and dense irregular connective tissue in the dermis is somewhat arbitrary--it's more like a gradient, but the professor always draws a line across the picture somewhere. Similarly, the clinician or laboratory or government agency decides what "healthy" is, and what "diseased" is.

It's very easy to think this, because our imaginations lend a lot of credence to it. But it's not true. Health and sickness are like virtue and vice or water and oil: immiscible. A healthy person is like a glass of water; a sick person is like a cup of oil. Granted, there are lots of kinds of oil, and some are less viscous than others and resemble water much more. (The analogy limps because a sick person can become healthy and vis a versa; last time I checked the literature, a cup of water cannot become a cup of oil.)

Another problem was the blatant assumption that disease is largely determined by culture. The lecturer quoted the subtraction of homosexuality from the DSM as an example. (In 1973, demonstrations and protests pressured the American Psychiatric Association to review the literature and vote on the diagnosis.) This is indeed an example of a culture determining what is called a disease. It is not an example of a culture determining what is a disease.

What is and is not a disease is not determined by any person or any culture. It is determined by the nature of man (the internal principle of motion). For instance: a mechanic determines whether or not a car is broken based on the car's intended function. He does not consult the cultural norms for what is accepted; he does not vote with his fellow mechanics about it. Similarly, physicians ought not to consult the cultural norms when they identify disease states, nor ought they to vote among themselves. The should consult man's nature and determine whether a state is compatible with man's natural (intended) function.

(As an aside: homosexuality doesn't take much thought if considered this way. Man is male and female by nature, and designed for heterosexual union.)

What was the APA considering in 1973? Previous to this lecture, I did not know. Now, I do: the qualification for mental disease is inability to function in life. (The lecturer cited an example to drive this point home: if a person presents with classical schizoprenia--hallucinations, delusions, genetic predispositions, the works--but can function normally, they don't have it. According to this speaker, most of the DSM entries are now modified with this criterion: the patient must be dysfunctional according to generally accepted norms.) Gays, the APA said in '73, were able to function and felt quite accepted and normal. Therefore, they were not mentally diseased.

There is no nature in psychiatry, and I fear there is little more in medicine.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

I baked a lasagna!

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Friday, August 12, 2011

Gross anatomy is still hard. We have had three labs now, but it has not gotten much easier for me. My sheen of nonchalance has gotten more convincing, and my tankmates even think I am a decent dissector (at least, they tell me so—perhaps it is more encouraging talk). But when I go into the lab after-hours to identify structures on different bodies, the smell still makes me ill. One body I opened tonight was particularly strong: a wave of plasticky chlorine, sick-sweet, hit me like a railway tie as I reflected the rib cage. My skin smells like it, too. And anything I lift to my nose smells like it for a few hours after I leave the lab. And because the water is soft here, I feel like I’m drinking that smell whenever I drink.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Armadillos and interviewees

I saw an armadillo today! I have never seen one before with my own eyes. It was noshing on some grass and I spotted it as I took my morning walk. To my surprise, it jumped away like a rabbit! In fact, it was completely like a rabbit, except that as it hopped across the road its armor scraped on the concrete a little.

I saw an armadillo today! I have never seen one before with my own eyes. It was noshing on some grass and I spotted it as I took my morning walk. To my surprise, it jumped away like a rabbit! In fact, it was completely like a rabbit, except that as it hopped across the road its armor scraped on the concrete a little.I also saw another type of rare, skittish creature today: interviewees! It's the first day of interviewing. I can't believe it! It feels like we just finished that whole circus. It's a year-round industry, this "get into medical school" thing. They all looked professional and smiley and happy. I saw some of them in interviews. Wow, what an important twenty minutes. I hope they all do well.

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Daily schedule

Quickie post:

Right now, my daily schedule looks like this:

6:45ish - wake up, take walk with anatomy or histology flash cards. Walk to mail kiosk, get mail.

7:20 - shower/get ready

7:40 - pray

8:00 - breakfast

8:15 - leave for school

9:00 - class

12:00 lunch/study

1:00 - more class

3:00 - more class or lab (some days), study (other days)

5:00 - stop studying, travel to St. Mary's Church

5:30 - Mass

6:30 - go home (or to anatomy lab), study

10:30 - do dishes, pack bag for tomorrrow, Vespers, and bed

And right now (I've gotta say) I'm loving every minute!! It is SO AWESOME to be studying what I love to study ALL THE TIME!! No more intervening stupid classes, it's all what I want to do. I am pretty much gleeful all day--gleefully serious, but gleeful. My only source of negativity is the possibility of failure. But I trust in Christ, who made heaven and earth. And really? Medicine doesn't make saints; union with Christ makes saints.

Right now, my daily schedule looks like this:

6:45ish - wake up, take walk with anatomy or histology flash cards. Walk to mail kiosk, get mail.

7:20 - shower/get ready

7:40 - pray

8:00 - breakfast

8:15 - leave for school

9:00 - class

12:00 lunch/study

1:00 - more class

3:00 - more class or lab (some days), study (other days)

5:00 - stop studying, travel to St. Mary's Church

5:30 - Mass

6:30 - go home (or to anatomy lab), study

10:30 - do dishes, pack bag for tomorrrow, Vespers, and bed

And right now (I've gotta say) I'm loving every minute!! It is SO AWESOME to be studying what I love to study ALL THE TIME!! No more intervening stupid classes, it's all what I want to do. I am pretty much gleeful all day--gleefully serious, but gleeful. My only source of negativity is the possibility of failure. But I trust in Christ, who made heaven and earth. And really? Medicine doesn't make saints; union with Christ makes saints.

@_@

Have I mentioned that there are about a zillion passwords and websites to remember?

- the site for viewing the histology slides (too cool for microscopes)

- Blackboard

- the M2s' resource site. More overwhelming than helpful?

- the facebook group

- the dropbox

- the yahoo listserv (so nineties, IMHO, but Matriculation thinks it's a great communication tool, so I don't complain)

- the site they use to quiz us in real time during class in their powerpoints (mildly nifty)

- the site I use to take notes on pdfs, since all the lecture notes are published in pdfs

- the site I view the recorded lectures on

- the analogue to blackboard to pool all my information for the Health Science center, which (btw) isn't actually part of the affiliated University. It's part of the university system. (I still get charged $101 for the university's rec center?)

- the medical science library webpage

- the university services (e.g. paying for parking permits)

- the HSC email

- the virtual private network, which I need to access before I view histology if I want to view from home

- the site for ExamSoft, the program through which I take all my exams.

Cadaver paper

I thought I would share one of my assignments with you. We had to write a paper for Medical Humanities about our cadaver. This will repeat some of the content of the August 3 post, but perhaps you will enjoy it anyway.

I was glad for the long orientation before the first Gross Anatomy lab, because I was afraid. I stood among my new friends around an object of some horror to me: a metal coffin—half gurney, half grave.

Outwardly I was very collected about this lab, because I am a Catholic Aristotelian. A Catholic knows that death is not our end, that the body is an inferior part which decays and will be regained miraculously. An Aristotelian knows there is substantial change, so a corpse is not a man and not of a man. No problems with dissection; no cause for fear.

Inwardly, I was a mess. I can’t say why. I have survived peers, professors, and relatives and never been so disturbed.

We opened the tank and raised the body. A skeletal figure showed through the towel, stiffened and slightly contorted. I saw the outline of a forehead, a nose, a chin. Arms, pelvis, legs. Then, I helped peel back the towel and I saw more. This body belonged to an old man: his skin was mottled on his arms and shoulders. His belly was sunken. I expect he lived some years in a nursing home. I spent a year or so of Sundays in a nursing home, visiting several residents. I was close to one woman in particular. She had the same skeletal frame and mottled skin.

He had a scar running along his midline, beginning four inches above his navel and curving around it. Someone suggested an abdominal aortic aneurysm, and my mental picture of this man’s life broadened, borrowing pieces from the story of my friend in the nursing home.

She came to the home following an ICU stay of two weeks for an emergency I can’t remember. “I died,” she would say when she told me the story. “I woke up and couldn’t remember any of it; I woke up and I was here.” She woke up with a colostomy. Later, they would remove all her teeth. She had not been outside in the intervening eighteen months. (Her family was not proactive about moving her home.)

But she was vibrant. She had been a WWII pilot’s wife and a Hollywood beauty. She had stories about Errol Flynn and D-Day (her husband flew over Normandy that day.) I sat enraptured whenever she talked. She like bright lipstick and nail polish. She loved art and history books. I loved her.

“People come here to die,” she observed one day. It was an uncharacteristic comment for her. I waited for her to say more, but she only repeated herself, then perked up again and asked me to read her WWII book aloud. A few weeks later, she died.

Maybe this man was like her: perhaps he changed his home and friends for a bed and CNAs. I’m sure he had a fantastic life story, and could tell of many sufferings.

In the lab, these thoughts did not erase my fear. I found some of my tankmates’ eagerness to dissect repulsive. Faced with any other body I would reverently pray. This seemed totally wrong.

But this man, like my friend who died, was generous. And I accept his gift—though not with ease—because of something my friend told me the last time I saw her. That Sunday, I told her I was accepted to medical school, and she began to cry. “Be a good doctor,” she charged. And I begin now.

I was glad for the long orientation before the first Gross Anatomy lab, because I was afraid. I stood among my new friends around an object of some horror to me: a metal coffin—half gurney, half grave.

Outwardly I was very collected about this lab, because I am a Catholic Aristotelian. A Catholic knows that death is not our end, that the body is an inferior part which decays and will be regained miraculously. An Aristotelian knows there is substantial change, so a corpse is not a man and not of a man. No problems with dissection; no cause for fear.

Inwardly, I was a mess. I can’t say why. I have survived peers, professors, and relatives and never been so disturbed.

We opened the tank and raised the body. A skeletal figure showed through the towel, stiffened and slightly contorted. I saw the outline of a forehead, a nose, a chin. Arms, pelvis, legs. Then, I helped peel back the towel and I saw more. This body belonged to an old man: his skin was mottled on his arms and shoulders. His belly was sunken. I expect he lived some years in a nursing home. I spent a year or so of Sundays in a nursing home, visiting several residents. I was close to one woman in particular. She had the same skeletal frame and mottled skin.

He had a scar running along his midline, beginning four inches above his navel and curving around it. Someone suggested an abdominal aortic aneurysm, and my mental picture of this man’s life broadened, borrowing pieces from the story of my friend in the nursing home.

She came to the home following an ICU stay of two weeks for an emergency I can’t remember. “I died,” she would say when she told me the story. “I woke up and couldn’t remember any of it; I woke up and I was here.” She woke up with a colostomy. Later, they would remove all her teeth. She had not been outside in the intervening eighteen months. (Her family was not proactive about moving her home.)

But she was vibrant. She had been a WWII pilot’s wife and a Hollywood beauty. She had stories about Errol Flynn and D-Day (her husband flew over Normandy that day.) I sat enraptured whenever she talked. She like bright lipstick and nail polish. She loved art and history books. I loved her.

“People come here to die,” she observed one day. It was an uncharacteristic comment for her. I waited for her to say more, but she only repeated herself, then perked up again and asked me to read her WWII book aloud. A few weeks later, she died.

Maybe this man was like her: perhaps he changed his home and friends for a bed and CNAs. I’m sure he had a fantastic life story, and could tell of many sufferings.

In the lab, these thoughts did not erase my fear. I found some of my tankmates’ eagerness to dissect repulsive. Faced with any other body I would reverently pray. This seemed totally wrong.

But this man, like my friend who died, was generous. And I accept his gift—though not with ease—because of something my friend told me the last time I saw her. That Sunday, I told her I was accepted to medical school, and she began to cry. “Be a good doctor,” she charged. And I begin now.

Friday, August 5, 2011

So different...

Medical school and TAC are very alike in that I feel like I study 80% of the time I'm awake. (Sometime, I should measure that.) The biggest difference I feel right now is the level of technology utilization. It's almost comical.

Fascinating. Which venue better facilitates education? Hm...

| TAC | Medical School |

| corkboards if an assignment changed, a scrap of paper went up: "Seniors IV.2 Coughlin: read pp 2-4 for Monday" | Blackboard 9 supposed to facilitate spreading of information...guess there's a learning curve |

| chalkboards there are two whiteboards on campus, but we don't talk about that. | huge screens these project the powerpoint, the lecturer, and anything else they want (qrayon it up!) |

| pens and paper even Aristotle would know what to do. | laptops, iPads, tablets the "old school" people type. all the cool people use styluses or their fingers. |

| "no recording devices are permitted" in the classrooms | every lecture recorded and posted "within 24 business hours" |

| books my last semester, the dean reviewed a request to allow kindles. the answer was a diplomatic "no." | bootlegged ebooks I have bought ONE physical book for my medical education. I have, like, sixteen ebooks. |

| class of <20 | class of 200 and I realize this is a step down for some of my peers... |

| you can see everybody and be heard from everywhere in the classroom | we videoconference with a location 100 miles away, and have to use microphones to be heard |

Fascinating. Which venue better facilitates education? Hm...

First day of Gross Anatomy

The first day of Gross Anatomy. This morning I put the hundredth mile on my second tank of gas. I put on old clothes. I had already made a trip to my locker at the Gross Lab building, so my coat and goggles and gloves awaited me. I packed my computer (et cetera) for morning classes, and left.

We had a late arrival and a short lecture before lunch. I had packed lunch and dinner because I planned to stay into the evening in the library to study. My lunch was a ham and cheese sandwich, which I ate as I reviewed the lab material (and copied ebooks off of one of my classmates’ USB keys). I felt all sick and solid inside, but tried to act normal and eat. It was a good thing the ham was the sliced-super-thin kind: it didn’t look much like muscle. And I tried to eat sort of fast, so that I could be finished (and have things into my duodenum) before the dissection.

Everyone I spoke to was excited. Some were excited but a little apprehensive, like I am before TAC finals. Some were excited and impatient—“I just wanna cut” was one man’s phrase. I found that repulsive, even though that’s how I was before cat dissections in college. (For the record, I never said, anything like “I just wanna cut.”)

I was only afraid, but I kept saying “excited” when people asked me. I wonder whether others were afraid.

We went into the lab. I felt like we were going to gas chambers: all lined up in a hallway, going in grouplets of six or nine into the Lab’s anteroom. (The anteroom , I believe is a precaution to protect the identity of those who donate their bodies. You must go through the first door into the anteroom, then wait for the first door to close before opening the door to the Lab. As a result, the suspense of the First Entry was hiked up to ridiculously high levels.) We must scan an ID to open the door, even during Lab hours. (After hours, we must scan it just to get into the building.)

I had seen the lab once, during interviews. It did not seem real then—just another room we were touring. All the tanks were closed (as they were when we walked in), and I didn’t give a thought to what was inside. Now, my brain was full of those thoughts. In each tank—a metal coffin on wheels surmounted by a computer stand—was a body. And I knew that they would look like the cats I’d dissected: stiff, strange, skeletal. Like death.

My tankmates raised our cadaver. (you depress levers at the head and foot of each tank to raise the body off the floor of the coffin and up to an operating-table height.) The body was covered in a thin white towel—thin enough so that they body could clearly be seen, especially the bonier prominences: long feet, knobby knees, the iliac crests, the ribs, shoulders, and the face. I was standing at the left shoulder of the body, and saw where the towel did not quite cover the left arm. It was a white arm with many dark freckles and fair, course hair. I knew it to be the arm of an older person. And I knew that our cadaver was a male from the outline beneath the towel. (Because the first dissection is the anterior chest, I was hoping that I would not be assigned to a female’s body.)

We had orientation for a long while, then the lab began. I wanted to busy myself fetching a computer for us to use, but I couldn’t delay the inevitable. Because I was at the head of the tank, I helped pull the towel off of the body to the waist. (The head, hands, and feet) were still wrapped in gauze; for this, I was very grateful.)

The smell invaded me. I felt ill and weak. I felt that it would be wonderful to lose consciousness, wake up, and find out that I would never have to do this again: you’re not in medical school, you’re here in the novitiate—what funny dreams you have! Nothing went away. I did not want to touch the body, but because of some funny streak in me I think I was the second to palpate the jugular notch and sternal angle. But throughout the entire lab, I was distracted and silent. I could tell that my tankmates gathered that I was timid and shy by nature, because their suggestions and tones were trying to gently tease me out. (“Here, you try; right there. Hey, that’s great. There you go!”)

The lab was mercifully short, because there weren’t many structures to identify, and one my tankmates has done human anatomy with cadaver dissection before. I went to wash my hands and could not wash them enough. I must have washed for a full minute (at least.) and after I left the lab and hung my coat in my locker, I went to the ladies’ room and washed my hands again.

I put a scrub top over my T-shirt and went to Mass. I slumped in the back of the church because I felt unclean. My mind was full of bodies and death, and those two ideas feature rather prominently in the Mass. This did not help me. After Mass, I sat, crumpled in my pew, and cried.

Two girls were sitting about ten pews in front of me, talking and laughing quietly. How interesting our lives are! When we are in heaven the three of us will look at this day and say that though our days were so different and our emotions so various, we were both sharing those minutes with Christ, all alone with His Heart.

After that, the day wound down. I went to the medical sciences library. I had no appetite at all, but realized that my packed dinner had gotten too warm to rerefrigerate at home. So I ate it in the café (which is undergoing construction or something—there’s some lovely exposed drywall where they ripped out the counters and food prep area entirely). The previous weekend, I’d made up dinners for the whole week and I’d brought one of these.

I am stupid. I knew that we would have our first Gross Anatomy lab. I knew that we would dissect the pectoral region. What did I pack? Chicken breast.

It was dry and bland and awful, and it made me sick and solid inside again. I didn’t even have a knife.

I dragged myself upstairs to study, and sunk into one of the big, poofy lounge chairs in the silent study area. What relief after standing for four hours in lab! I studied until ten and forgot all about it. I went home; Vespers was comforting; and I fell into bed.

We had a late arrival and a short lecture before lunch. I had packed lunch and dinner because I planned to stay into the evening in the library to study. My lunch was a ham and cheese sandwich, which I ate as I reviewed the lab material (and copied ebooks off of one of my classmates’ USB keys). I felt all sick and solid inside, but tried to act normal and eat. It was a good thing the ham was the sliced-super-thin kind: it didn’t look much like muscle. And I tried to eat sort of fast, so that I could be finished (and have things into my duodenum) before the dissection.

Everyone I spoke to was excited. Some were excited but a little apprehensive, like I am before TAC finals. Some were excited and impatient—“I just wanna cut” was one man’s phrase. I found that repulsive, even though that’s how I was before cat dissections in college. (For the record, I never said, anything like “I just wanna cut.”)

I was only afraid, but I kept saying “excited” when people asked me. I wonder whether others were afraid.

We went into the lab. I felt like we were going to gas chambers: all lined up in a hallway, going in grouplets of six or nine into the Lab’s anteroom. (The anteroom , I believe is a precaution to protect the identity of those who donate their bodies. You must go through the first door into the anteroom, then wait for the first door to close before opening the door to the Lab. As a result, the suspense of the First Entry was hiked up to ridiculously high levels.) We must scan an ID to open the door, even during Lab hours. (After hours, we must scan it just to get into the building.)

I had seen the lab once, during interviews. It did not seem real then—just another room we were touring. All the tanks were closed (as they were when we walked in), and I didn’t give a thought to what was inside. Now, my brain was full of those thoughts. In each tank—a metal coffin on wheels surmounted by a computer stand—was a body. And I knew that they would look like the cats I’d dissected: stiff, strange, skeletal. Like death.

My tankmates raised our cadaver. (you depress levers at the head and foot of each tank to raise the body off the floor of the coffin and up to an operating-table height.) The body was covered in a thin white towel—thin enough so that they body could clearly be seen, especially the bonier prominences: long feet, knobby knees, the iliac crests, the ribs, shoulders, and the face. I was standing at the left shoulder of the body, and saw where the towel did not quite cover the left arm. It was a white arm with many dark freckles and fair, course hair. I knew it to be the arm of an older person. And I knew that our cadaver was a male from the outline beneath the towel. (Because the first dissection is the anterior chest, I was hoping that I would not be assigned to a female’s body.)

We had orientation for a long while, then the lab began. I wanted to busy myself fetching a computer for us to use, but I couldn’t delay the inevitable. Because I was at the head of the tank, I helped pull the towel off of the body to the waist. (The head, hands, and feet) were still wrapped in gauze; for this, I was very grateful.)

The smell invaded me. I felt ill and weak. I felt that it would be wonderful to lose consciousness, wake up, and find out that I would never have to do this again: you’re not in medical school, you’re here in the novitiate—what funny dreams you have! Nothing went away. I did not want to touch the body, but because of some funny streak in me I think I was the second to palpate the jugular notch and sternal angle. But throughout the entire lab, I was distracted and silent. I could tell that my tankmates gathered that I was timid and shy by nature, because their suggestions and tones were trying to gently tease me out. (“Here, you try; right there. Hey, that’s great. There you go!”)

The lab was mercifully short, because there weren’t many structures to identify, and one my tankmates has done human anatomy with cadaver dissection before. I went to wash my hands and could not wash them enough. I must have washed for a full minute (at least.) and after I left the lab and hung my coat in my locker, I went to the ladies’ room and washed my hands again.

I put a scrub top over my T-shirt and went to Mass. I slumped in the back of the church because I felt unclean. My mind was full of bodies and death, and those two ideas feature rather prominently in the Mass. This did not help me. After Mass, I sat, crumpled in my pew, and cried.

Two girls were sitting about ten pews in front of me, talking and laughing quietly. How interesting our lives are! When we are in heaven the three of us will look at this day and say that though our days were so different and our emotions so various, we were both sharing those minutes with Christ, all alone with His Heart.

After that, the day wound down. I went to the medical sciences library. I had no appetite at all, but realized that my packed dinner had gotten too warm to rerefrigerate at home. So I ate it in the café (which is undergoing construction or something—there’s some lovely exposed drywall where they ripped out the counters and food prep area entirely). The previous weekend, I’d made up dinners for the whole week and I’d brought one of these.

I am stupid. I knew that we would have our first Gross Anatomy lab. I knew that we would dissect the pectoral region. What did I pack? Chicken breast.

It was dry and bland and awful, and it made me sick and solid inside again. I didn’t even have a knife.

I dragged myself upstairs to study, and sunk into one of the big, poofy lounge chairs in the silent study area. What relief after standing for four hours in lab! I studied until ten and forgot all about it. I went home; Vespers was comforting; and I fell into bed.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)